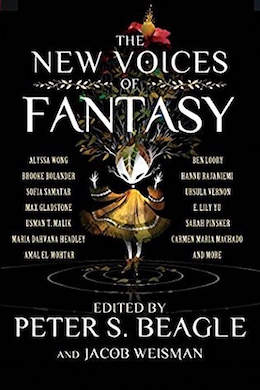

Jacob Weisman notes in his introduction to The New Voices of Fantasy that it is, in some sense, a successor to Peter S. Beagle’s previous anthology The Secret History of Fantasy (2010)—a follow up on the idea of an exploding field of literary fantastic stories appearing over a wide range of publications. This collection focuses specifically on writers who are in the early stages of their careers, with all stories included “published after 2010.” Considering the seven-year range that encompasses, it’s a bit broader than a new-writers collection focusing on folks in their first few years of publication.

However, this also gives Weisman and Beagle a wealth of stories to choose from to represent the tone and caliber of the movement they’re pointing to in fantastic fiction. These are charming stories, often focused on the personal experience of a character, and all are fantastical in scope rather than scientific, though their approaches do have some variation. The New Voices of Fantasy includes stories in modes from the mythic to the horrific, with some traditional approaches mixed in as well.

Several of these stories I’ve reviewed previously in original publication or, in one case, myself been the editor for in original publication. Shared among them is a certain delicacy or lightness of touch: sometimes this comes across in the fragility of the magical elements such as in “Wing” by Amal El-Mohtar, and sometimes it’s in the themes of otherwise direct pieces like “Jackalope Wives” by Ursula Vernon. Thematics are a connecting thread in these disparate pieces—frequently concerned with gender, race, and culture, these stories bring in a broader range of perspectives, nations, and approaches to the idea of the fantastic.

Initially, I read without consulting which publications the given stories or writers had come from. As The New Voices of Fantasy mixes liberally between stories published in-genre and stories that come from mainstream literary pastures, it seemed prudent to leave myself in the dark about the origin of the works I was reading. There are interesting slips between the modes, of course, with several writers occupying both “sides” of the field in turns. However, two of the stories from mainstream publications were remarkably similar in their concern with fatherhood from a masculine perspective that was somewhat myopic and ultimately frustrating.

While I enjoyed the general concept of “The Philosophers” by Adam Ehrlich Sachs, the execution was dull and self-involved at best—the sort of story I’ve read in a hundred creative writing classrooms. The use of disability as a fantastic trope also itched at me a bit in a way it’s hard to pin down. “Here Be Dragons” by Chris Tarry was nominated for the Pushcart prize, and certainly has its moments of interest, but in the end I found the piece’s romantic approach to the protagonist to be offputting. There are moments where the text is aware of his failure and his flaws, but those are fundamentally subsumed in favor of his desire to go off and live his glory days again. The flutter of an argument or criticism of the character turns on itself to become a reification of the thing that it initially seemed to be critiquing, and also, I have very little sympathy for this equally self-involved perspective.

Otherwise, however, I found the stories to be engaging, varied, and somehow well-matched despite their differences. Some pieces that stood out which I have not previously discussed are “Hungry Daughters of Starving Mothers,” which also is concerned with mothers and fathers but in a much more self-aware and ultimately awful fashion. These characters, monstrous as they are, have responsibility to each other and a sense of consequence and cost for their selfishness, unlike the protagonist of “Here Be Dragons.” I also appreciated “Left the Century to Sit Unmoved” for its lack of closure and its approach to family; it gives the reader the same sensation of jumping into the pond that might disappear a person that the protagonist has—damn skillful.

Max Gladstone’s “A Kiss With Teeth” tackles fatherhood, marriage, and the fantastic as well, with a firm sense of responsibility and consequence—plus, it’s damn funny as a concept: Dracula raising his son with his suburban ex-vampire-hunter wife. “The Husband Stitch” by Carmen Maria Machado is also about families and parenting; moreso, it’s about men’s thoughtless hunger and ownership of women, and ends exactly as awful as you think it will. The point is rather clear.

Truly, issues of parenting and families appear in a large number of these stories, perhaps as a result of the editors’ efforts to include stories that contain a deeply personal element—none of these pieces are shallow action-oriented romps. All, even the silliest of the bunch, are invested primarily in character dynamics in general and often familial attachment in specific. The total result is a collection that leaves the reader with a thoughtful sensation, the idea that these stories have all worked their way in deep but subtly. Nothing here is wrenching; everything here is designed to prod gently at the emotional involvement of the audience.

It’s an interesting choice, and I don’t know that it represents the whole of new fantastic fiction, but it certainly represents a specific and hard to define corner of it. The inclusion of the longest piece, Usman T. Malik’s “The Pauper Prince and the Eucalyptus Jinn,” is a fine choice in this vein—it closes the volume, which is not where I’d expect to see the most hefty of the stories included, but it works. Having this engaging, clever, often-breathtaking story as the closing note leaves the reader with a solid echoing sense of the book, one I appreciated thoroughly.

The editors have done a solid job of collecting a range of a specific type of fantastic story that has grown popular in recent years. Though each of these pieces differs, sometimes significantly, from the others, the collection as a whole is remarkably cohesive in terms of affect and intention. I’d recommend it for anyone who has an appreciation for the literary fantastic or stories about families, and especially both.

The New Voices of Fantasy is available now from Tachyon Publications.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. They have two books out, Beyond Binary: Genderqueer and Sexually Fluid Speculative Fiction and We Wuz Pushed: On Joanna Russ and Radical Truth-telling, and in the past have edited for publications like Strange Horizons Magazine. Other work has been featured in magazines such as Stone Telling, Clarkesworld, Apex, and Ideomancer.